Emperor’s Cup is ready for another round to take place, but the competition’s history has been long and deep. So please enjoy the third contribute of this column by Tobias Dreimann (you can follow him on Twitter @ConDrei), who’s gonna follow the steps throughout history of one of the oldest football tournaments in Asia.

When you think about Japanese football, your first thought may be about the Japanese national team, called “Samurai Blue”, or the J. League, Japan’s pro-football competition. The first being the world-known display of Japanese football with competitive players, the latter today’s prime competition this blog’s common reader learned or learns to love for its passion, entertainment value or colorful variation of mascots.

While the question about the inception in Japanese football is quite an interesting topic to look into, the development of Japanese football in the early 20th century has always been defined by one competition that is still one of the oldest worldwide – or is it? For the 100th anniversary of the Emperor’s Cup, I wanted to take a look at the birth of the competition and analyze how it mirrored the development of Japanese football up to this day.

With basic research possibilities due to the language barrier, I wanted to provide some basic knowledge about this traditional cup competition that I grew so familiar with by simply entering the history into the Transfermarkt data base. Follow me on the journey I took for the 100th edition of the Emperor’s Cup. If you’re looking for the first and second part of this column, you can find it here and here.

The first 10 years of the JFA national football final saw the tournament abolished once in 1926 while regularly merged with the Meiji Shrine Games, a sport championship that became the most important of its time. With university sports programs regularly winning the JFA national football final, association football in Japan started to be formed by those successful teams ahead of WWII. The first derbies were established, colonized areas were integrated into the competition with a few Korean teams and player that were raising eyebrows, but also the level of the sports.

Up to now in our trip down memory lane, the JFA national final is not known as the Emperor’s Cup.

Post-WWII: the “Industrial Revolution” of football

After the heavy destruction of the country and the reorganization of a social order, the Emperor lost his political power and started to morph into the representative role he holds today. While the country was rebuilding itself, the JFA organized a first shy attempt to make football part of the reconstruction. Was it the lust for normality that drove some teams back into the scene so quickly? The JFA was able to start with two qualification groups. The Kanto region had eight teams participating, while Kansai raised interest with four teams.

Both group winners took part in the single game that was called the “1st Reconstruction All Japan Championship” by the JFA in 1946 and replaced the national final that year. Tokyo University Light Blue (LB) returned after a 15-year long absence against a short-term replacement team from Kansai. The qualified mixed alumni team from Kyoto and Osaka University was not eligible to participate in the final, so the runner-up, Kobe Keizai University, briefly booked a night train to the capital to face the Kanto winners. May it be because of the short preparation, Kobe Keizai lost big with a 6-2 blowout loss to Tokyo University LB.

To this day, the Emperor’s and Emperess’ Cup was a formal patronage to different sports competitions, where one of them handed over the silverware with the chrysanthemum emblem to the respective winner. Apart from sumo and baseball – both were never patronized by the Imperial heir since their early days – there were no boundaries on which competition would then be patronized by the Emperor or his wife. The first example was a horse racing event in 1905.

The 1946 match officially was denominated the “1st Reconstruction All Japan Championship”, under a different name it would then take place for several years rebranded as the “East-West Opposition Match”. One year after the JFA brought football back the Emperor attended the East/West final on April 3rd, 1947, as a spectator. Despite the small tournament, which officially did not run as the JFA national final, the Emperor was impressed by the match and considered a patronage which was formalized by July 1948.

Back then, the JFA received the official Emperor’s Cup title from the Imperial Houshold Agency and was allowed to build their tournament around the name of the Emperor. Because of civil unrest in the previous years, the JFA was not able to organize a nationwide national final which led to the dismissal of the tournament from 1947. With the new title in hand, the Emperor’s Cup trophy was awarded to the winner of the East-West Opposition Match.

The 29th Emperor’s Cup – or was it already?

1949 was the second year after WWII that the JFA held a national final in Japan. The Imperial patronage in hand the JFA national final still was not known as the Emperor’s Cup, as the silverware was handed to the winner of the East-West Opposition match as long as it lasted. Only when in 1951 the East-West match was abolished the trophy was handed to the winner of the JFA national final. This, basically started the Emperor’s Cup legacy from then on.

Yet, the JFA did not only want to give the upcoming victors of the competition the title “Emperor’s Cup winner”, but also praised all previous winners as title holders. Therefore, with its inaugural game in 1921 and as you, dear reader, are aware that 2020 is the 100th year of the Emperor’s Cup, one might wonder how is that feasible.

Just two years before, in 1947 and 1948, there was no tournament. If it wasn’t only for the years of WWII, you might remember there were some years when no tournament was played – therefore, no winner to be crowned. My personal take is, as the Emperor’s Cup patronage in general is a diffuse collection of patronages to several competitions, so this prestigious title can be given at any year to any winner in any patronized competition.

If there wasn’t an Emperor’s Cup winner in football, there might although have been one with rugby or horse racing, giving the patronage a validation for that year anyway. So as the odds of the past broke the continuous timeline of the now patronized competition, yet it did not harm the Imperial prestige handed to the JFA in 1948.

Furthermore, as you might notice, since 1949 there was no disruption of the Emperor’s Cup tournament. Not even in this strange time in 2020 where the COVID pandemic almost forced the JFA to call off their 100 years-jubilee, the Emperor’s Cup/national final will be given… but more on that later: back to the sports!

On June 4-5, 1949, the Emperor’s Cup was held with several participants nearby Tokyo; not in the metropolitan area, but on the grounds of the Waseda University’s Western campus. Contestants hailed from five different regions in Japan: Tokyo University LB from Kanto, an alumni team from Aichi Commercial High School, the sports team from Kansai University and for the first time two company-led teams.

Apart from the Emperor’s patronage two years later, this is a significant caesura in the Japanese football world. After WWII, Japan lived through an economic boom. Companies at that time demanded a lot of work force from their employees, but because of their good situation were also able to give certain guarantees like life-long job security and to a certain degree of sports and activity compensation. The students from the years before were now part of that work force and many companies established their own company football teams.

Nitettsu Mining from Kyushu Region and Toyo Industries from Chugoku Region were the first company owned-clubs that were represented in the JFA national final, yet both lost their semi-finals against those football-shaping university teams. Tokyo University LB claimed their second title by winning 5-2 against the Kansai University alumni, while Toyo Industries won the third place play-offs match.

The fire sparks: football takes life all around Japan

In 1950 the competition was expanded to 16 participants, its highest to that date. Also for the next 15-ish years, the final round would be held in different cities all over Japan with a local host club automatically set for the tournament. The 30th edition Emperor’s cup was played in a baseball stadium in Kariya, in the Aichi Prefecture. The participants qualified from all nine Japanese regions, while Kanto, Kansai and Chubu regions had two participants each. Given how Tokyo was the JFA’s hometown and most influential city for football in the past decades, it had an additional 10th qualification tournament.

While the Tohoku region was not able to send a member club to Kariya, Sapporo club from Hokkaido remained absent from the tournament, which brought Nittetsu Mining an instant win in the the first round. While still a lot of mixed teams from universities all over Japan took part in the tournament, and Nitettsu mining as the sole company owned team was crushed 7-0, it was the Keio University team that went all the way, reaching the final against a Kwansei Gakuin University mixed team. The final 6-1 loss prevented Keio University to win their second title since 1937 on their last qualification.

In 1951 the tournament moved from Kariya to the Miyagino Ward in Sendai Prefecture. Ten teams qualified via their regional tournaments, while four teams, including a host club from Sendai, were selected by the JFA. Keio BRB faced a club from Osaka, but ultimately won the tournament by 3-2. The following year the tournament moved from Sendai to Fujieda in Shizuoka Prefecture and 16 teams became the new standard for the following 10-ish years. Unfortunately, Hokkaido FA was not able to determine a participant, which left their place vacant and resulted in an automatic progression for the all-Rikkyo University football team.

While researching through all those years, I often met those university teams with a Japanese全 “zen” (means “all”) character before the university name. It appears those teams differed from the official university football teams, but I am not sure in what way. I assume those teams were scouted out of several students that not necessarily are connected to the official university football program.

While you might argue they are still a football team from that particular university, the JFA noted that 1951 all-Rikkyo university team had their inaugural appearance to the tournament while Rikkyo University premiered in the 1961 tournament. Therefore, you not only have to differ e.g. between Keio University and Keio BRB as an alumni team consisting of former students, but also between those two entities and the all-Keio University football team that also participated (as Keio BRB) on the 1951 tournament.

This becomes crucial when we discuss the number of titles Keio University won. While even today Keio University might be named as the most successful participant of the Emperor’s Cup, collecting nine trophies in total, those titles have been won by different teams of that university. Anyway, in the end Osaka Club met the all-Keio University football team that was admitted by a JFA and therefore ultimately won the tournament.

Played in Kyoto, near Kyoto Sanga’s Nishikyogoku stadium, 1953 almost saw all 16 teams participate in the national final if it wasn’t for the Hokkaido-based Muroran Club that, even though they won their qualification round, couldn’t make it to the former imperial city. This tournament, however, saw future Nagoya Grampus Eight manager Ryuzo Hiraki (managing the club between 1992 and ‘93) win the Emperor’s Cup with the all-Kwansei Gakuin University football team. Remember his name for later.

Based this time in the Prefectural Baseball Stadium in Kofu, Yamanashi prefecture, the 1954 edition of the Emperor’s Cup saw the first company-owned team play in the finals. Sanfrecce Hiroshima’s predecessor, Toyo Industries Soccer Club, faced Keio BRB, one of the most prestigious teams of the tournament (having already won the Emperor’s Cup four times). It was a difficult game that finished 1-1 after 90 minutes. In the first of four overtimes in total, both teams scored twice which ended as a 3-3. As there was no penalty shootout yet it took Keio BRB three additional periods, a total of 170 minutes of playing time, to finally win 5-3 and therefore their fifth Emperor’s Cup title.

Moving to Nishinomiya between Osaka and Kobe, the 35th edition of the Emperor’s Cup featured mostly university and alumni teams. Nevertheless, corporate teams became more regular as Toyo Industries was accompanied by Nippon Steel and Nippon Light Metal. None of those three moved up the ladder much, since in the end All-Kwansei Gakuin University team won their second title in four years.

Omiya, Saitama Prefecture, hosted the 1956 edition of the Emperor’s Cup. This year brought the turning point in Japanese football history: the pendulum started to swing away from university football to corporation-defined football teams. Toyo Industries and Nippon Steel both progressed to the semi-finals where Kyushu-based Nippon Steel Yawata progressed against the Chuo University “Old Boys” and Toyo Industries lost against Keio BRB. The final match on May 6th, 1956, finished with a 4-2 win for Keio BRB who won their 6th and, after all, last Emperor’s Cup title.

The tournament also saw a first appearance by a small squad from Kyoto: Kyoto Shiko Club. The team, originally founded in 1922 by a group of middle school alumni, returned to the scene in 1937 under the name “Kyoto Shiko Soccer Club”. In 1954, it was rebranded as Kyoto Shiko Club and in about 40 years in the future it will be the foundation on which Kyoto Purple Sanga will be founded. Even today, a club called Kyoto Shiko Club plays in the Kansai Regional League, keeping the original name and its tradition alive.

It’s all about the company: a game changer

12 years after suffering the devastating atomic bomb, Hiroshima hosted the Emperor’s Cup on the Kokutaiji High School Stadium in the city’s Naka Ward. As hosts Toyo Industries were automatically qualified, it was Nippon Tabacco Hiroshima that qualified via the pre-tournament: an early exit was their fate as they lost to Chuo University’s “Old Boys” in the tournament’s first round. Toyo Industries, like Chuo University Old Boys, reached the final scheduled on May 6th, 1957. Still it was the alumni team that won against the locals and one year after reaching the finals Chuo University Old Boys lifted their first and only Emperor’s Cup trophy.

1958 saw the Emperor’s Cup return to Fujieda, Shizuoka Prefecture. Nippon Steel Yawata progressed to the finals, where they lost against Kwangaku Club, an alumni team from Kwansei Gakuin University who ultimately won their first national cup title. More importantly, in 1959, Kwangaku Club defended their title and won against the real Chuo University football team.

Even though it was Toyo Industries that won their 3rd place matchup a second time, it was another company team in the mix that marked their first success in the Emperor’s Cup: Furukawa Electric Soccer Club. The team was founded in 1946 by Furukawa Electric, a company that since the 1900s maintained an ice-hockey team in Nikko, Tochigi Prefecture. Since 1914, those sportsmen from Nikko regularly played soccer, but never grew as a team.

It were Tokyo-based employees of Furukawa Electric that In the 1930s , in their spare time, played soccer and intended to start as a company team in the fourth division of the Kanto Company League in 1941. Because of the Pacific War, though, those employees have been recruited for the military and the idea was postponed. Almost half a decade later, Furukawa Electric Soccer Club build up what would ultimately become JEF United Chiba Ichihara, one of the 10 founding members of Japanese professional football – and the only team that never was relegated from first division football until the infamous 2009 J.League season.

Managed by Ken Naganuma, Furukawa Electric SC aimed high in 1960. By winning 6-0 against another corporate club, Teijin SC, and 3-0 against regular Nippon Steel Yawata SC, Furukawa met the Meiji University’s football team in the Emperor’s Cup semi-finals. With a 6-1 win, Furukawa Electric scored 15 goals in three matches, only conceding one. Nevertheless, when they faced Keio BRB in their attempt to win their 7th title, it was a 4-0 bashing that led to the first Emperor’s Cup title won by a corporate team ever.

Ken Naganuma, a football mastermind

Born in Hiroshima in 1930, Naganuma studied at Kwansei Gakuin University and won the tournament once in 1950 with the university’s mixed team. When he left Kwansei Gakuin University in 1953, he continued to study at Chuo University in Kanto. Naganuma progressed as a footballer from early on, participating in the 3rd international student week (predecessor to the Universiade) in Dortmund followed by a two months stay in Europe.

When he graduated from Chuo University in 1955 and before working for Furukawa Electric, a Kanto-based company that delivered their products to Hiroshima based Toyo Industries and Chugoku Electric Power, he was one of the rare players with a great football education. He helped Furukawa Electric to build a competitive team including some of their ice-hockey players, but with a straight plan to upgrade to higher-class football players annually. It was in 1957 when the company hired Ryuzo Hiraki as an employee who combined perfectly with Naganuma.

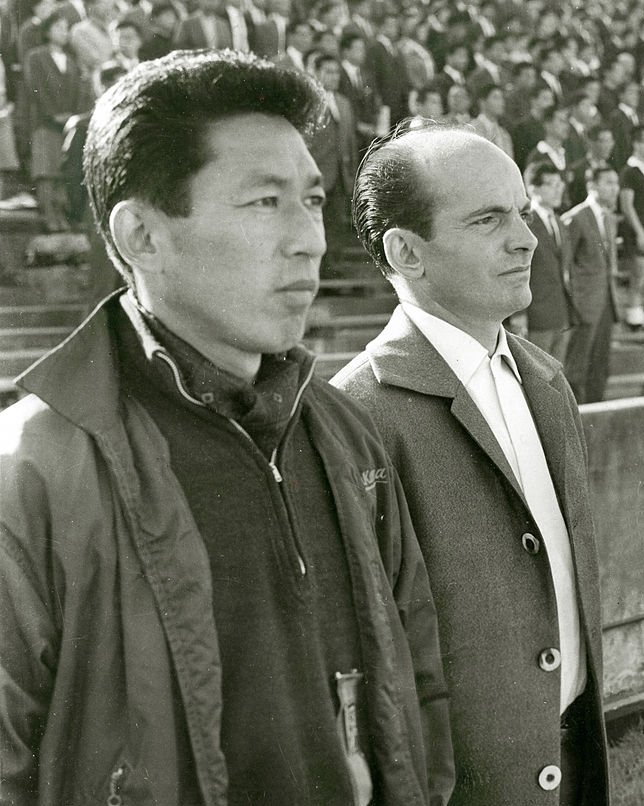

In 1959 Ken Naganuma officially named playing manager for Furukawa Electric and led the team to its first national title the year after. At 32 years old, he would become manager of the Japanese national team for almost 14 full years. He worked together with Dortmund-born Dettmar Cramer, who’s still today seen as one of the most influential people in modern Japanese football. Naganuma became JFA’s vice president in 1987 and president in 1994, helping to set the country up for the 2002 FIFA World Cup after a very turbulent time. Cramer, Naganuma and Ryuzo Hiraki were all enshrined to the JFA Hall of Fame in ‘05 for their significance on contribution to Japanese football.

In 1961, the strength of corporate teams became obvious when three out of four teams in the semi-finals were company-owned. In the end, Chuo University met Furukawa Electric SC in a final match that was won by Ken Naganuma’s side 3-2. The third place-match was decided between Toyo Industries and Nippon Steel Yawata. In 1962 the Emperor’s Cup returned to Kyoto, after having moved from Tokyo (1959) to Osaka (1960) and Fujieda (1961). It was the last time the tournament was to be played out between 16 teams.

Chuo University was again the only non-corporate team in the Emperor’s Cup semi-finals and had to face Toyo Industries. Meanwhile, Furukawa Electric had to face Nippon Steel Yawata. After 90 minutes there was no winner, leading to extra time where Ken Naganuma and his team were able to progress to the final. After losing the year before, the Chuo University team got its revenge against Furukawa Electric: On May 6th, 1962, the university club won by 2-1 to claim their only Emperor’s Cup title in history. On the other hand, Furukawa Electric failed to win the Emperor’s Cup for three consecutive years, a series that to this date no team has yet achieved.

The tournament changes

After the inception, the JFA National Finals were mostly played in May or June. Even though the competition schedule started in October in the 1920s, it mostly took place in the heat of the Summer and was only moved in its later years a couple of times to September/October or the following year when a catastrophe occurred. 1963 brought a new schedule to the Emperor’s Cup, starting in January of the following year. The number of participating teams was also reduced. 1963 had four company-owned teams out of seven teams participating, yet Waseda University won their second Emperor’s Cup title against Hitachi Soccer Club (later Kashiwa Reysol).

Both 1963 and 1964 Emperor’s Cups were held in Kobe, but the mode in the second year changed significantly. The JFA noticed a shift in the world of Japanese football. Two environments were competing to state the superiority of their respective football programs: universities as the grass roots basis of the nation’s football education, and company-money funded football clubs that were built around former students. Those two sides more regularly faced off in the Emperor’s Cup.

While football in the last decades was shaped by students and university football, it progressed under the financial superiority of the company teams. It was still some years before league football started in Japan, but the JFA wanted to implement this battle between football cultures into the Emperor’s Cup’s iteration. 1964 saw ten teams compete in a never before seen manner: five university clubs and five corporate teams mixed in two groups, facing each opponent once with only the best two of each group to play for the final match and the 3rd place in a playoff round.

The progress of corporate football became clear as only Waseda University was able to qualify for the playoffs, but ultimately lost their 3rd place match against Toyo Industries. The final between Furukawa Electric and Nippon Steel Yawata saw no winner at all. No penalty shootout invented at this time, 1964 to this date marks the only mutual title win in Emperor’s Cup history.

With the first success of the Japanese national team on the international stage, football became a national interest. The JFA had high interest in improving the national football culture. With the rise of company football in Japan and the successful launch of a national league in Germany (also long-lasting league football in England, France and Italy), the idea for a national football league grew and resulted in the foundation of the Japan Soccer League in 1965. Prior regionalized tournaments were still happening, but with corporate football, the JFA launched a steady competitive project, aiming to compete with baseball in the Land of the Rising Sun.

Those teams were about to gain dominance in Japan and the Emperor’s Cup, formerly known as the JFA national final. When I started to learn about Japanese football the competition was simply called Emperor’s Cup and I didn’t spend much time or thought onto finding out about its roots or anything. The retroactive rebrand of the JFA national final never occurred to me before researching for this series. Somehow, I assume the JFA, too, remembered their roots and what I didn’t noticed before writing this text: in 2018, the JFA changed the logo of the Emperor’s Cup. Instead of the ball logo, subtitled by 天皇杯 („tennouhai“, jap. “Emperor’s Cup”) the logo now is framed in blue, written in white “Emperor’s cup”, followed by an additional text. This text states: “JFA Championship”.

If you find any mistake or may correct some of my research, please feel free in doing so. For the game results please have a look at the Emperor’s Cup history on Transfermarkt.com.

2 thoughts on “Emperor’s Cup: a century of history (Part 3)”