Emperor’s Cup is ready for another round to take place, but the competition’s history has been long and deep. So please enjoy the fourth contribution of this column by Tobias Dreimann (you can follow him on Twitter @ConDrei), who’s gonna follow the steps throughout history of one of the oldest football tournaments in Asia.

When you think about Japanese football, your first thought may be about the Japanese national team, called “Samurai Blue”, or the J. League, Japan’s pro-football competition. The first being the world-known display of Japanese football with competitive players, the latter today’s prime competition this blog’s common reader learned or learns to love for its passion, entertainment value or colorful variation of mascots.

While the question about the inception in Japanese football is quite an interesting topic to look into, the development of Japanese football in the early 20th century has always been defined by one competition that is still one of the oldest worldwide – or is it? For the 100th anniversary of the Emperor’s Cup, I wanted to take a look at the birth of the competition and analyze how it mirrored the development of Japanese football up to this day.

With basic research possibilities due to the language barrier, I wanted to provide some basic knowledge about this traditional cup competition that I grew so familiar with by simply entering the history into the Transfermarkt data base. Follow me on the journey I took for the 100th edition of the Emperor’s Cup. If you’re looking for the first and second part of this column, you can find it here, here and here.

After the JFA national tournament was established in 1921 the competition was held almost annually, only to be scrapped from huge social issues like the death of the Emperor or WWII and the country’s rebuilding. When the war ended the national final was played once but paused in favor of an annual rebuilding tournament. In 1947, after the Emperor visited one of those matches it was the Imperial Household agency itself that offered the JFA its famous Emperor’s Cup title to give it to their prime tournament.

1949 was logically the first JFA national final that was held under the name of the Emperor’s Cup but with its long tradition the competition was overhauled and every winner since 1921 was named Emperor’s Cup title holder.

A seismic shift from university clubs to corporate teams followed the strong economic of post-war Japan. Former participating students that now were part of the work force established teams within their companies and brought success to their parent companies. To finalize this shift further steps awaited.

“It’s the Sixties, man!”

Even today Dettmer Cramer, former assistant coach of the Japanese national team, is said to be one of the most influental figures of Japanese football. It was his suggestion that Japan cannot develop a football culture if they don’t have a national league competition. Most university football association declined to feature in the league, but Cramer’s idea was to duplicate the “Regionalliga” concept he knew from his native country, Germany. Since Japan already posessed a well-built Shinkansen railway network, he suggested to have competing teams from anywhere those bullet trains stopped and call it a “National League”.

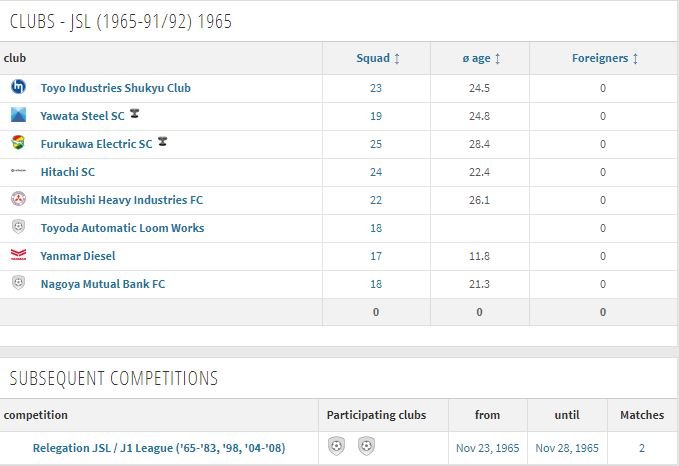

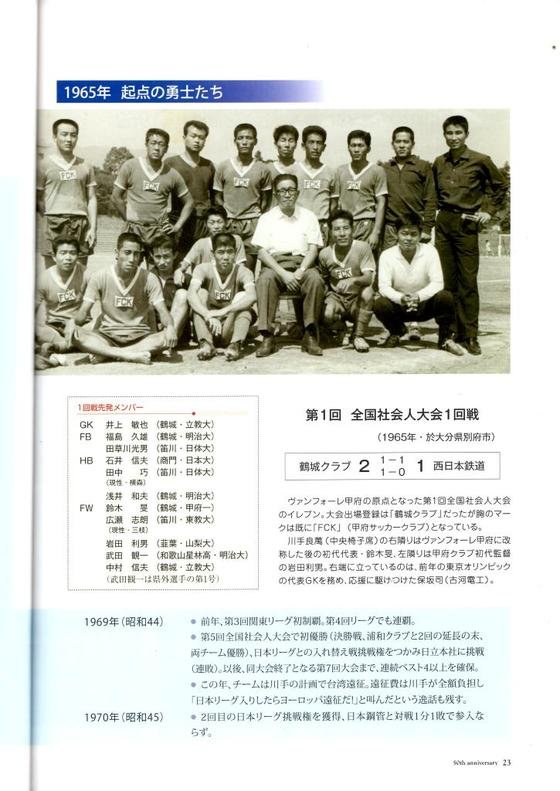

The name “Japan Soccer League” was established with the hope to have university teams involved at some point, yet only corporate teams started in the maiden season of JSL, in 1965. It has been rumoured that Ken Naganuma, former national team coach, invited Waseda University to participate who really were interested in the first place. Yet they couldn’t figure out to work around the university’s own league schedule, where the team also had to participate. Kickoff of the first tournament Japan Soccer League round was June 6th, 1965.

With JSL established as a full-season competition, the Emperor’s Cup 1965 was moved to January 1966 to be played at Komazawa Park stadium in Setagaya, Tokyo. Since the battle for football supremacy between corporate teams and university clubs was established within the last couple of years, the idea was to see it running in the Emperor’s Cup tournament. Therefore the first round was played out between the four best JSL teams and the best four university clubs of that year.

Two of the coprorate teams (Toyo Industries, today’s Sanfrecce Hiroshima, and Yawata Steel) and two of the university clubs (Waseda and Kwansei Gakuin universities) progressed to the semi-finals. Yet Toyo Industries smashed Kwansei Gakuin University by 7-0, while Yawata Steel’s win over Waseda was much closer. In the end, Toyo Industries won the 1965 Emperor’s Cup, but they also clinched the first JSL title, making them the first team to snatch the domestic double of Japanese football history.

While the impact of Hiroshima football on the Japanese football scene deserves a different investigation and there will probably be a future piece on this blog at a later point, Toyo Industries in the mid-60s became the first football dynasty of the country. Winning five of six JSL titles between 1965 and 1970, Toyo Industries became an unstoppable force under manager Sachio Shimomura. This was a subsequent step up from the high profile the team already showed in the Emperor’s Cup editions before the start of the JSL.

1966 was going to be the last year a university team could lift the trophy of the Emperor’s Cup. The split starting field of 1965 returned but apart from Waseda University all other semi-finalists have been corporate teams. Against Toyo Industries Waseda won by 3-2 on January 15th, 1967, while that title ended an era of Japanese football history.

The new normal

The 47th Emperor’s Cup was going to be the last tournament moved into the following year in its entirety. The split starting field faced some minor issues, as both Furukawa Electric (runner-up of the JSL) and Yawata Steel (4th) declined their participation in the Emperor’s Cup due to unknown reasons. Hitachi would have then qualified as the 6th placed team, but they also declined.

In the end, it was Nippon Kokan that hardly kept their JSL Div. 1 assignment by drawing both their relegation matches against Nagoya Grampus’s predecessor Toyota Motor. Kansai University was able to progress to the semi-finals, but the final was a full corporate matter. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries was defeated 0-1 by Toyo Industries on January 14th, 1968 who won their second Emperor’s Cup title in three years.

In 1968 Mexico hosted the Olympic Games, where 16 football teams from all over the world qualified. Over 273 amateur players in total played for medals and represented their home country. Years before the Olympic Committe discussed the nomination of World Cup participants, as the Olympic Games should remain an amateur sports tournament. For Japan, who clearly didn’t have that kind of experience in 1968, there were no boundaries though.

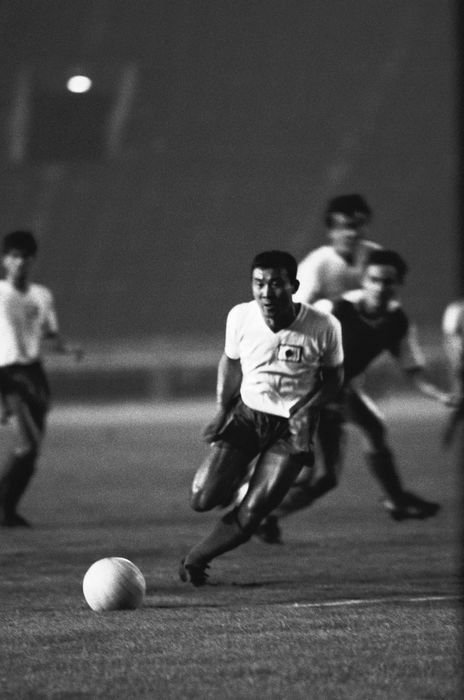

Ken Naganuma, former Furukawa Electric player, could field the best players avilable from the newly founded Japan Soccer League. The matches for the football tournament were scheduled between October 13th and October 26th, 1968, in four locations: Mexico City, Puebla, Leon and Guadalajara. Japan faced off highly favorites Spain and Brazil as well as Nigeria. Yet, Japan made it to the knock-out stage, a first success that is highly connected to a 24-year old player from Kyoto: Kunishige Kamamoto.

By clinching a hat-trick against Nigeria in the first Olympic match, Kamamoto will ultimately become the golden boot winner by scoring seven goals throughout the tournament. Even today, Kamamoto is regarded as one of the most influental figures of Japanese football history, having played for the Waseda University between 1963 and 1967, which led him to his employer’s team Yanmar Diesel (today’s Cerezo Osaka) that same year.

While Yanmar Diesel haven’t won the JSL title yet, 1968 was about to become a special year for Kamamoto and the club. Almost relegated in 1966, it was also Kamamoto’s influence that helped Yanmar Diesel turn their fate around and finish 1968 in the JSL as a runner-up. They also reached the Emperor’s Cup final to play against Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. It took the teams to expansion time before Yanmar Diesel could lift their first trophy in history on New Year’s Day of 1969.

Corporate rivalries

Speaking of dynasties, in that regard we are not talking of a decade of dominance. As described before, it was Toyo Industries from Hiroshima that shaped the early years since the JSL inception in 1965. While that lasted until 1970, Japanese football was then defined by the teams Yanmar Diesel and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries. While both couldn’t build a real dynasty, their rivalries raised the game to higher levels. The JFA, still with the “university v. corporate” rivalry in mind, lacked the urgency to adapt, but the Emperor’s Cup showed a lot of drama for teams in search of national glory.

In 1969 a tradition was established that even holds today: from this year on, all final matches were held on New Year’s Day of the following year. Also the tournament was mostly held in the National Stadium in Tokyo instead of rotating venues nationwide.

The split between corporate teams and universities continued for several years. Between December 21st, 1969 and January 1st, 1970, the 49th Emperor’s Cup was held in Tokyo. Rikkyo University’s football team featured in the final match, thanks to a 3-3 draw against Yawata Steel in the quarter finals. By lottery it was decided Rikkyo would face previous finalist Mitsubishi, yet won 2-1 against the corporate team. In the end, Toyo Industries dominated the game and won 4-1 against the university team. It would be the last title for Toyo or his successor Sanfrecce Hiroshima in the Emperor’s Cup.

The 50th Emperor’s Cup in 1970 was shortened to six days. In the first round, all university teams lost, leaving it between the corporate teams to decide a winner. Yanmar faced Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, yet had to rely on their luck, to progress by lottery to the final against Toyo Industries.

The Hiroshima team was highly favorited due to the sheer dominance they maintained through Japan Soccer League even winning their last JSL title in 1970. It was Kunishige Kamamoto though who scored the first goal of the match to give the Osaka side an advantage. Toyo Industries was able to equalize but again Kamamoto scored the match winner by head to win the second cup title for Yanmar Diesel.

In 1971, the split university/corporate tournament was played one last time before the JFA backed up from that idea, probably due to the fact that for the second time in a row not a single university team could qualify for the knock-out stage. It was the end of the culture clash between university and corporate football with a clear winner. After Yanmar regularly won against Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in recent years, the 51st trophy was their’s to hold.

With the concept scrapped, the JFA was in search for a different look for the tournament. Instead of limiting the finals to a handful of teams, the JFA decided to expand the competition to a total of 24 teams (three times the number of the previous year). All Japan Soccer League Div. 1 clubs qualified automatically, while the teams of the newly founded second tier had to qualify in their regional tournaments. University teams likewise had to qualify by region.

That year Kofu Club (Ventforet Kofu’s predecessor) and three university teams were able to qualify: Keio, Waseda and Chuo University. The tournament was organized like the British F.A. Cup and started in a straight knock-out competition, yet with more teams to participate the schedule was extended from December 10th, 1972 to January 1st, 1973. In the first round, regional qualifiers competed for a spot in the second round where they were to meet all eight JSL teams.

Yet, the dominance of corporate football teams became obvious again as none of those teams could compete for a quarter final spot. The JSL teams were left to play for national cup glory and on New Year’s Day 1973 the final was held between Yanmar Diesel and Hitachi Soccer Club (today’s Kashiwa Reysol). Like in the JSL Hitachi SC was victorious after 24 year-old Yoshitada Yamaguchi and 22 year-old Akira Matsunaga turned the game.

By expanding the JSL to 10 teams the 53rd Emperor’s Cup in 1973 qualifiers were raised by two. Because of this expansion, two regional teams had to be pre-eliminated via two new first round matches. Again not a single regional qualified team made it to the quarter finals, which stressed the dominance of corporate football. While Hitachi reached the final they had to concede against Mitsubishi Heavy Industries 1-2 who win their first national double.

Kamamoto, the legend

1974 was the year Kamamoto became a living legend. Thanks to 21 goals in 18 JSL matches Kunishige Kamamoto, now 30 years of age, not only won his fourth golden boot, but also reached over 100 goals in the 10 years of Japan Soccer League football. Yanmar Diesel started in the third round of the tournament, where they faced Nagoya Soccer Club, a lower league team from that city that even today plays in the Tokai Soccer League.

An easy 5-2 win paved their way to the quarter finals where Yanmar won 3-0 against competing JSL side Nippon Kokan. The 2-0 semi-final win against Mitsubishi Heavy Industries led to their fourth final appearance against Yamguchi-prefecture based Eidai SC. Eidai Industries’ football team, a company today based in Osaka, debuted that year in Japan’s first tier and the title chance in the Emperor’s Cup was about to become their biggest shot since its inception two years before.

Thanks to the help of three Brazilian players, Eidai went all in on their campaign, yet Kunishige Kamamoto spoiled their plan by scoring the 2-1 victory goal for Yanmar Diesel. Winning the JSL that same year, it was Yanmar’s first national double and coincidentally the third national double in a row by three different teams.

The 55th Emperor’s Cup was not too special. Yanmar was defeated by Hitachi that won their second cup title against Fujita Industries (today’s Shonan Bellmare). But this gives us some space to look at something different: The development in the lower divisions and non-league football was exciting to watch at that time. In 1973 a total of 75 teams competed in the regional qualifying rounds. Within one year, all over Japan a total of 807 teams applied at the JFA to compete in their local tournament.

Before the 1976 tournament, the JFA had applicants of over 1,353 teams nationwide. All of them eligible to qualify for the Emperor’s Cup – for only 26 spots. Football grew in popularity and the grassroots development thrived despite the dominance of corporate football. It turned out the JFA by adjusting the Emperor’s Cup to an FA Cup-like tournamen opened the door to a grassroots football movement in those years.

On the corporate side though Yanmar Diesel faced Furukawa Electric (today’s JEF United) on New Year’s Day 1977. Kunishige Kamamoto, who already won his 6th golden boot in the JSL 1976 season, and his team lost 4-1 to Furukawa Electric. Especially 25 year old Yasuhiro Okudera raised some eyebrowes, scoring 36 goals in 100 games recorded since 1970. Long before Kazuyoshi Miura moved abroad to become a pro footballer, it was Okudera who moved to Cologne to become the first Japanese player to play in a European top league.

In 1977 the Emperor’s Cup was expanded once again to 28 teams. This removed the additional first round of past years. Yanmar Diesel who contributed much to the rise of corporate football had to play against Fujita Industries, a relatively new company in the JSL as they promoted in 1972 to the first division.

Yanmar on the other hand was founded in 1957 and has been a permanent participant to the Japans Soccer League since its inception. Yet Kamamoto grew of age, 33 going into this tournament, and even though he was going to play until he became 44, the recent dominance vanished. Between 1971 and 1975, Yanmar Diesel won three JSL and three Emperor’s Cup titles.

Between 1968 and 1977 Yanmar competed seven times in the Cup finale, yet the 57th final game in the Tokyo National Stadium against Fujita Industries was lost again by 1-4. It would take 40 years for Cerezo Osaka to revive the memorial Yanmar Diesel built in those years. It will be remembered by Hall-of-Fame enshrined Kunishige Kamamoto and his teammates Kenji Onitake, Nelson Yoshimura and Shu Kamo.

Apart from the downfall, Yanmars who already lost on penalties in the quarter-finals the 1978 Emperor’s Cup had its own oddities: With Yanmar club, for the first time a reserve team participated in the cup competition, qualified via the regional tournament. Yet the second team of the company didn’t succeeded their parent club’s history. It had to be a loss against Fujita Industries that removed Yanmar Club from the tournament. Toyo Industries, that removed Yanmar Diesel lost against Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.

Yanmar Club qualified another time next to JSL Div. 1 seeded Yanmar Diesel, and coincidentally both clubs reached the quarter-fnals. Yanmar Diesel won 3-0 to Furukawa Electric, yet lost again to Fujita Industries in the semi-finals. Yanmar club already failed at the quarter-finals. You can only imagine of both teams had focused their power into one squad. Maybe they had stood a chance.

Uproar of the minors

A new decade opens but not much has changed for the Emperor’s Cup. The Japan Soccer League still was seperated in two divisions since 1972, the JSL Div. 1 was won by Yanmar Diesel for the last time, and to honor the 60th edition of the Emperor’s Cup the JFA expanded the competition once to 30 teams. First, the winner of the JSL Div. 2 was handed a qualification spot, second, Hosei university as winner of the annual university cup was granted rights to play in the Emperor’s Cup, too.

Yet, the most intersting team was Tanabe Pharmaceuticals, a JSL Div. 2 team that qualified via the Kansai regional qualification round. Winning against Div. 1 Teams Honda Motors, Yanmar Diesel, Toyo Industries and Yomiuri FC (via penalty shootout) the small team against all odds reached the final against Mitsubishi Industries. Early in second half Tanabe conceded the crucial goal the cost them the underdog title win. Since its inception in 1972 no Div. 2 team has won the Emperor’s Cup.

But we only had to wait for the year 1981 when Div. 2 winner Nippon Kokan qualified via the regional cup for the Emperor’s Cup. Again a Div. 2 team reached the cup final. The biggest difference though was that Nippon Kokan was not an underdog in a traditional way. Indeed the team was relegated from JSL Div. 1 for the first time in 1979, when they lost the relegation match to Yamaha Motors (today’s Jubilo Iwata) by penalties.

Winning the Div. 2 title was not far fetched and Nippon Kokan faced of Sapporo University, Fujita Industries, Honda Motors and Tsukuba University on their way to the final. And indeed, dear reader, Tsukuba University was the first university team to reach the Emperor’s Cup semi-finals in more 10 years.

Against Yomiuri FC (Today’s Tokyo Verdy), Nippon Kokan faced a soon-to-be football dynasty. But at this time, that legacy was still to be made. Nippon Kokan could defend their lead over Yomiuri and became the first non-first-division team to win the Emperor’s Cup. Only to be followed by 2011 FC Tokyo, that won against fellow J.League Div. 2 club Kyoto Sanga on New Year’s Day 2012.

We steadily progress towards the inception of the J.League but still there are ten years left. After corporate teams shaped the Japanese football landscape and started to dominate the Emperor’s Cup these clube are going to be the foundation on which the J.League will be founded.

If you find any mistake or may correct some of my research, please feel free in doing so. For the game results please have a look at the Emperor’s Cup history on Transfermarkt.com.

One thought on “Emperor’s Cup: a century of history (Part 4)”