Emperor’s Cup is ready for another round to take place, but the competition’s history has been long and deep. So please enjoy the fifth contribution of this column by Tobias Dreimann (you can follow him on Twitter @ConDrei), who’s gonna follow the steps throughout history of one of the oldest football tournaments in Asia.

When you think about Japanese football, your first thought may be about the Japanese national team, called “Samurai Blue”, or the J. League, Japan’s pro-football competition. The first being the world-known display of Japanese football with competitive players, the latter today’s prime competition this blog’s common reader learned or learns to love for its passion, entertainment value or colorful variation of mascots.

While the question about the inception in Japanese football is quite an interesting topic to look into, the development of Japanese football in the early 20th century has always been defined by one competition that is still one of the oldest worldwide – or is it? For the 100th anniversary of the Emperor’s Cup, I wanted to take a look at the birth of the competition and analyze how it mirrored the development of Japanese football up to this day.

With basic research possibilities due to the language barrier, I wanted to provide some basic knowledge about this traditional cup competition that I grew so familiar with by simply entering the history into the Transfermarkt data base. Follow me on the journey I took for the 100th edition of the Emperor’s Cup. If you’re looking for the prior parts of this column, you can find it here, here, here and here.

When the JFA was established their national final, it was the beginning of Japanese association football on a broader scale. Mostly university and school teams made up the participants until after the war, when the JFA national final was rebranded as the Emperor’s Cup. Former students, now part of the work force, and the economic rise of Japan were an integral part to set up corporate teams that led to a shift in Japanese football culture.

Those teams grew more competetive and overtook as the nations driving force of football. This strength was demonstrated by the first national football league, Japan Soccer League, in 1965 which consisted only of corporate teams and improved the Japanese national team to win bronze in the 1968 Mexico Olympics. Several teams competed in the JSL and the Emperor’s Cup througout these decades, but the next major shift was in the making.

On the brink of professionalism

Neither England, Germany or most other countries where football grew as a business, the payment for athletes was regularly a topic of tense discussions. The only difference concerned which was the epoch in which those discussions arose. When football grew popular at the end of the 19th century, English entrepeneurs had interest to promote their brand by the help of a successful football team.

To bring good players to their teams, it became common to put them on a payroll, but this brought some controversy. The Netflix series “The English Game” narrates this (yet shows little actual football happening), focusing on the social issues between the nobility and rising working class.

Half a century later, Germany faced the same discussions, when in 1920 an entrepeneur family challenged the German FA (Deutscher Fußball-Bund or DFB) with their plans to form a professional league. After their bankruptcy, the DFB – who behind closed doors did indeed work on a pro league draft – was tempted to doubled down on the amateur ideals of the DFB for several decades to come.

Players and officials were regularly banned by the DFB, while payroll players and transfer fees in the dark grew an imminent part of national football. Only by establishing proper contracts before the inaugural Bundesliga season in 1963/64. the situation changed drastically and opened the door to professional football.

Japan’s way to professionalism has already been paved by many other countries, yet the corporate and therefore amateur nature of Japanese football and the JSL was a burden yet to overcome. In 1981 Nippon Kokan was the first 2nd division team to win the Emperor’s Cup. In 1982, Yamaha Motors (today’s Jubilo Iwata) who have been relegated the year before, had no hard time winning the JSL Div. 2 championship.

By qualifying via the Tokai tournament, Yamaha Motors could focus on the Emperor’s Cup to win the tournament like Nippon Kokan did before. After wins against Toshiba, Fujitsu, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and finalist Yomiuri FC, Yamaha faced Fujita Industries in the final game. A volley goal by Mitsunori Yoshida in expansion time was enough for Yamaha Motors to clinch their first major title. It would be the last time non first-tier team won the Emperor’s Cup until 2011’s FC Tokyo.

The Nissan-Yomiuri decade

The 28 teams-format was played out a last time in 1983. While Yanmar Diesel gave other competitors some heat, it was a rather small team out of nowhere that surprisingly went all the way to the finals. Nissan Motors, a corporate team from Yokohama, started ten years before in 1972. Heavily funded, within seven years the team moved all the way up from Kanagawa prefecture league Div. 2 to JSL Div. 1. Since their first appearance in the Emperor’s Cup in 1977 Nissan Motors failed to move past the second round, yet, after a troubling 1982 season where Nissan finished in 8th place domestically, 1983 indeed was the first year when they showed the true potentional of that team.

In 1983 Nissan Motors were runner-ups to the JSL Div. 1 championship and the JSL League Cup. In the Emperor’s Cup first round a 7-1 win over Tanabe Pharmaceuticals set the tone for the rest of the December cup campaign. Shu Kamo, former player at Yanmar Diesel, had his team play pedal to the metal, as wins against Teijin (4-1), Fujitsu (6-0) and Fujita Industries (3-2) brought Nissan Motors straight to the finals. On New Year’s Day it was of all teams, Yanmar Diesel, they faced in the Tokyo National Stadium. The 2-0 win over Kamo’s former team was the kick-off for a decade that concentrated national cup glory on two teams, Nissan Motors being the first.

Yomiuri Giants are the biggest club in Japanese pro baseball history. Up to that point in history, Yomiuri won 23 national titles in 34 seasons of the Nippon Professional Baseball (founded in 1950). The team name “Giants” hints at what the self-perception of Yomiuri back than was (and probably still is). The rising popularity of football since the inception of the Japan Soccer League, Yomiuri planned to establish a second “giant” team in a major sport in Japan.

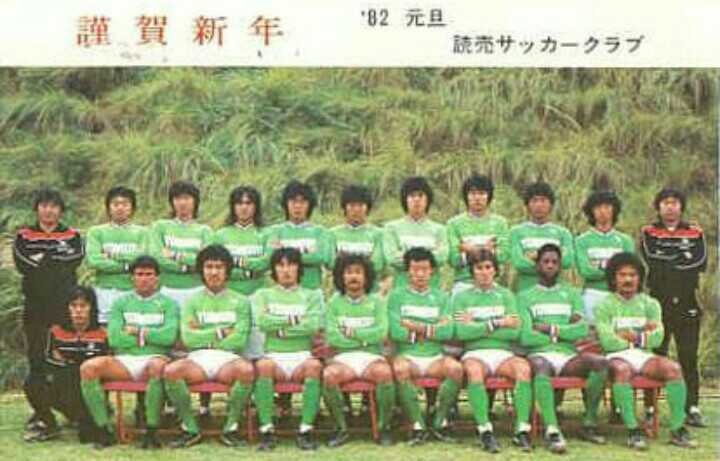

Yomiuri FC, was founded in 1969 and by the help of Dutch coach Frans van Balkom made it to JSL Div. 2 where several relegation battles ultimately failed. They moved up to JSL Div. 1 in 1978 and were able to establish themselves quite comfortably in Japan’s top football tier. Yet far away from the Giant status Yomiuri had in the baseball world. The year before, in 1983, Yomiuri won their first JSL title and 1984 German manager Rudolf “Rudi” Gutendorf took helm on the Kawasaki outfit. FC Nippon, the self-proclaimed nickname gives it away, wanted to claim the same superiority Yomiuri Giants already were, so there is no surprise that Yomiuri was able to defend their league title.

The Emperor’s Cup that followed their successful campaign was a walk in the park. Two goals conceded in the tournamnet, Yomiuri won against Osaka University of Health and Sport Sciences (2-1), Teijin (5-0), Yanmar Diesel (2-0) and Fujita Industries (2-1) to face former power house Furukawa Electric in the New Year’s final match. 26 year-old Ruy Ramos, 32 year-old George Yonashiro and 21 year-old Satoshi Tsunami, all future managers of the J. League, helped the team to lift the trophy that day. Goal scorer that day were Tetsuya Totsuka and Scotsman Steve Paterson. The first national double for Yomiuri FC and a first step for their yet-to-be-written legacy.

Let’s talk about pro football

In 1984 the total participants were upscaled to 32 and 1985 was no difference. The corporate dominance – not surprisingly – still remained from 1966. Officially all players were amateurs, yet more and more foreign managers and players were to be seen on the corporate team squads. Especially Yomiuri FC was infamous for having players on their roster that were not part of the company’s work force. As in Europe decades before, the discussion about professionalism in football needed to be hold.

The Japanese FA in 1985 admitted to those rumors and opened the regulations for teams to maintain a certain number “licensed players”. There were three categories players were subdivided into: “licensed players”, “non-amateurs” and “amateurs”. The rule change influenced the nature of Japan Soccer League significantly. Yasuhiko Okudera, who went to Germany to become a pro footballer returned, Kazuyoshi Miura, who moved to Brazil at the age of 16, gave his comeback with FC Nippon, Yomiuri, and foreign players became more regular on Japan’s pitches.

Shu Kamo, manager of Nissan Motors, who is responsible for the club’s rise to fame since 1974, was about to become the most prestigious manager of the Emperor’s Cup. A season to forget in 1984 was followed by a league cup final appearance and the succesful Emperor’s Cup campaign in 1985. Wins against Niigata Eleven (6-0, today’s Albirex Niigata), Hitachi (2-0), Nippon Kokan (5:4 on penalties) and 5-0 (Mazda) led to a final against Fujita Industries. Shu Kamo and his team opened the game with a volley goal by Kazuki Kimura, while Koichi Hashiratani doubled the lead that remained untouched.

With the first steps towards professionalization of Japanese football, the JFA wanted to assist the teams and changed something that J.League fans regularly discuss for their favorite football league. The schedule was aligned to the European calender. This influenced the Emperor’s Cup as the competition was played in the winter break halfway in the season. So JSL clubs couldn’t focus on the cup anymore. This helped a few amateur teams to try their best against those teams.

A Teacher’s Club from Hyogo prefecture (later, Banditonce Kobe/Kakogawa, today’s Cento Cuore Harima) was indeed able to move up to the quarter finals. Because Furukawa Electric remained absence from the game, Hyogo Teacher’s club moved to the second round where they met local coporate Team of Osaka Gas. Aimed for the stars the team was put back to reality by Yomiuri as they unsympathetically crushed the team by 5-0.

The supposed final of the tournament was held on Tuesday, Dec 30th, 1986, when Yomiuri faced Nissan Motors in the semi-finals. Both winners of recent years where high-favorites on winning the cup, especially since the second game was played out between Honda FC (yep, that Honda FC) and Nippon Kokan, two clubs with a mediocre quality in the league and cup history. After 120 minutes neither Yomiuri nor Nissan Motors could decide the game, as it was a 1-1 draw. On penalties it was decided within the first 4 penalties for Yomiuri as one player for Shu Kamo’s side missed the goal. Yomiuri won their second Emperor’s Cup title under now manager George Yonashiro.

The closer we move towards 1992, the more we get to know the teams, that were about to shape the J. League. One of the most prestegious teams of the younger Japanese football history was relatively new to the JSL scene. Sumitomo Metal Industries started their first kickball team in 1947, but integrated the football team to the company in 1956. As the team played in Osaka it took until 1974 to move up to JSL Div. 2, where they hardly could challenge for promotion.

Only a footnote in the company’s history but decisive for the future of the team, the head offices of Sumitomo Metal moved from Osaka to a small industrial town on the coast of Ibaraki prefecture. After moving up to the national competition and a single Osaka based 1974 campaign, Sumitomo Metal FC played their matches in the small town of Kashima, in the Ibaraki Prefecture. In 1985 Sumitomo Metal first entered the top tier of Japanese football, but was relegated the same year.

A brief return for the new, autumn/spring season format to JSL Div. 1 helped Sumitomo Metal to automatically qualify for the Emperor’s Cup. Wins against Kyoto Sangyo University (5-0), Yanmar Diesel (3-1) and Toshiba (6-4 on penalties, today’s Hokkaido Consadole Sapporo), Sumitomo Metal reached the semi-finals where they unfortunately lost to Mazda 1-2. It was between the Hiroshima team and Yomiuri FC on New Year’s Day 1988 to decide who would win the 68th Emperor’s Cup.

Yomiuri had Yasutaro Matsuki, Hisashi Kato, Satoshi Tsunami, Ruy Ramos and Tetsuya Totsuka on their roster. Names that are still remembered from those succesful years of soon to be Verdy Kawasaki. It was Totsuka who scored the second goal to help Yomiuri clinch their third Emperor’s Cup title in four years. Mazda, former Toyo Industries, on the other hand was still in wait for any national title after their impressive early years after World War II.

The final chapter of corporate football

The giant match of the tournament took place in the quarter finals as Yomiuri faced Nissan Motors once again prematurely. After goalless 120 minutes it would be decided on penalties as Nissan Motors won by 4-3 from the spot. The final between Fujita Industries and Nissan Motors couldn’t be decided in 90 minutes, but two goals in expansion time meant Nissan Motors won the third Emperor’s Cup title in six years.

In 1989, defending champion Yomiuri and Nissan Motors met once again prematurely in the semi-finals. While the winner was likely to win the tournament the second semi-final was as equally as interesting for what could have been. Another Yokohama-based team played against Yahama Motors (today’s Jubilo Iwata), but ANA/Sato Labs Yokohama lost 5-3 on penalties. This prevented the second major derby final in recent times, as Yomiuri and Nippon Kokan, both Kawasaki-based, met in 1986. Nissan Motors won the final game 3-2 and defended their previous title.

While the most recent tournaments were won either by Nissan Motors or Yomiuri FC and therefore showed the dominance of Kanto-based teams in the competition, one exception was the 70th Emperor’s Cup in 1990. A year prior Matsushita Electric was promoted to JSL Div. 1 and the team from Osaka prefecture was very motiviated. The first match against zip producers YKK was won 9-2, the second round against Juntendo University by 2-0 and Kokushikan University, that made it to the quarter finals by beating Yomiuri of all teams, was beaten 2-1 by Matsushita Electric.

As the Osaka team and Nissan Motors both won their semi-finals the New Year’s match in the Emperor’s Cup was played out between those two. A goalless draw in expansion time had a penalty shootout in favor of the newcomer that won their first, yet also – kind of – their last title in Emperor’s Cup history.

Behind the scenes a major shift was in preparation. The Japanese FA intended to start a full professional football league as the enthusiasm with crowds grew bigger and bigger. Especially the national team, dubbed the “Samurai Blue”, reached some significant attendance figures and to cash in on this development, J.League was about to be formed. All interested teams had to overcome some preperations to start in the first 1993 season, yet, we want to focus on the most significant one:

National professional baseball started in 1950, over 40 years prior to the J. League, yet the corporate identy of those clubs was tradition, like it has been for Japanese football teams since JSL started in 1965. To become grassroot sport in Japan, the JFA decided to abolish the corporate identity and appeal to some minor markets, that were not already occupied by pro baseball. Clubs should integrate into their home community which was hindered by the corporate identy that teams to that point had.

One of those first applicants to the J.League regulation was Matsushita Electric. The company that to a later point would rebrand to Panasonic shut down their corporate football team and founded a seperate soccer company in 1991. As Yanmar Diesel’s team already occupied Osaka City, Gamba Osaka moved to the northern city of Suita, where the 1970 Expo exhibition area has been rebuilt to a sports facility. The new name has not yet been established, but Matsushita would finish the process within an one year time span.

The transition phase

Kickoff for the 1991 Emperor’s Cup was Dec 14th where all winners of the past decade, Matsushita, Yomiuri and Nissan Motors, won their first round games. As title holders, Matsushita lost in second round against Mitsubishi Motors (former Mitsubishi Heavy Industries) so the final match between Yomiuri and Nissan has not been a surprise. Nobuhiro Takeda opened the scoreline for Yomiuri but Nissan Motors turned the table in no time as four goals by Everton Nogueira, Kazushi Kimura, Takahiro Yamada and Carlos “Renato” Frederico sealed the deal for their fifth Emperor’s Cup Title.

The 1991/92 season enlaced the 1991 Emperor’s Cup and was the last season of JSL football in Japan. After 27 seasons the most successful teams have been Toyo Industries/Mazda from Hiroshima by winning 5 JSL titles in the early years of the tournament. Followed by Mitsubishi Motors, Yanmar Diesel and more recently Yomiuri FC with 4 JSL titles each. The history of Japan Soccer League is still one to research on, but to understand the beginning of the J. League you may see the continuity from JSL as an integral part.

In Summer 1992 the outsourced football companies of the JSL era started their rebrand. Matsushita Electric was named Gamba Osaka and mainly consisted of former players of Yanmar Club, the Yanmar Diesel reserve team. Rumor has it the color scheme should resemble Atalana Bergamo in the Seria A, yet we know the logo was copied from an English lower-tier football team.

Yomiuri FC, the self proclaimed FC Nippon, rebranded as Verdy Kawasaki, which pointed at their common green color schemes. Nissan Motors renamed Yokohama Marinos while local rivila ANA/Sato Labs’ team was presented as Yokohama Flügels. To kick-off the new pro league and bypass the half year break that was necessary to return to the annual schedule, J.League Cup was established and matches were played all over Japan. Verdy Kawasaki won the first League Cup but the Emperor’s Cup was a different story.

The 10 founding members of J.League met some corporate and amateur teams that will some years down the line be founding members of J.League Div. 2 and a couple University teams. Apart from Bellmare Hiratsuka (former Fujita Industries), all teams in the quarter final would be participants in the inaugural J. League season, including newly founded Shimizu S-Pulse. This team that was not rooted in corporate football, but was founded as a nod to the successful football history and culture of Shizuoka Prefecture.

Verdy Kawasaki faced Urawa Red Diamonds in the semi-finals, while Yokohama Marinos had to play against Bellmare Hiratsuka. Both favorites won their matches and led to another Japanese “Classico” in the final. Marinos had to bring it to expansion time to win 2-1 against Verdy.

1993 was the next chapter of association football in Japan. Since the early days, over 70 years ago association football moved a long way from a small national tournament established by the Japanese FA to the engine that fueled the progression of the sports all over the country.

When you look at the Emperor’s Cup data on the Transfermarkt website you will see that the mutual record winner are Urawa Red Diamonds and Yokohama F. Marinos with seven titles each. Likely to be remembered Keio University with a total of nine wins was seperated by us for all three teams, Keio University, Keio BRB and Keio Club. Yet we decided to not seperate Urawa Red Diamonds from Mitsubishi Motors/Heavy Industries or Gamba Osaka from Matsushita Electric. Why is that though?

- The influence those clubs had on Japanese football, moving the amateur corporate teams towards full professional clubs is not to be underestimated. While the clubs of course were outsourced to fit the regulations of the J.League they were still heavily tied to their former corporation, their legacy should in our eyes not be seperated from the club they are today

- When copying the Emperor’s Cup history from Japanese wikipedia, we noticed the column 出場チーム, where all participants of a tournament where listed. The team name was followed by a number in brackets (10回目)which displays the total participating seasons within the tournament. In 1993 Kashima Antlers was playing the Emperor’s Cup for the 10th time, a continuation of their former Sumitomo Metal identity. This is not the same for the three Keio clubs where each one posesses its own count.

The history of Japanese football will be extended on Transfermarkt’s database as time progresses and more sources are digged up. So feel free to browse around the Japan Soccer League since 1965 or the Emperor’s Cup since 1921. Any help or corrections, either on the data or the text series you read here, is highly appreciated.

For the final text we are going to summarize the last 27 years of the Emperor’s Cup up to this year’s 100th edition. Thank you for staying with us.